Michael Langan shares his tips for editing your own work.

Editing is more, much more, than cutting, or polishing, or tidying, or re-structuring etc… it IS writing; everything else is just preparation for editing. It’s perhaps in the editing process that you discover who you are as a writer because there are times when it’s hard, hard work and if you’re still prepared to go through it, and come out the other end, you might just have a chance.

To read your work as a reader, to obtain some kind of critical distance, requires some time away from the work. I understand that this isn’t always possible, especially when working to a deadline, but, ideally, you would build some time into your writing schedule – even if it’s just one day – for ‘proving’, that is allowing the writing to rest, to settle, to grow in you mind and of its own accord. It makes the whole process more organic. By that, I mean, it takes it away, slightly, from the purely functional and gives the writing space to breathe and live of its own accord.

The novelist Julian Gough wrote in The Stinging Fly about the importance of ‘reading your work in slow motion’, and paying very close attention to every single word on the page. Pay attention at the level of the word, the phrase, the sentence, the syntax, the punctuation, the paragraph, the page, the scene, the section, the chapter, the beginning, the middle, and the end, the whole story, the whole work.

As well as reading in slow motion, reading your work aloud to yourself can be a very important, even vital, part of the editing process. Joanne Harris, author of Chocolat and many other novels calls this ‘the best editorial tool you have’. If it doesn’t quite sound right to you as you read it, then it doesn’t read right. You’re testing the work on many levels when you do this; its authenticity and verisimilitude, its order and ‘sense’, its structure, the rhythms and cadence and music of its language. As Harris says, “Clunky dialogue; overlong description; too many adverbs – Reading aloud shows them all up like magic.”

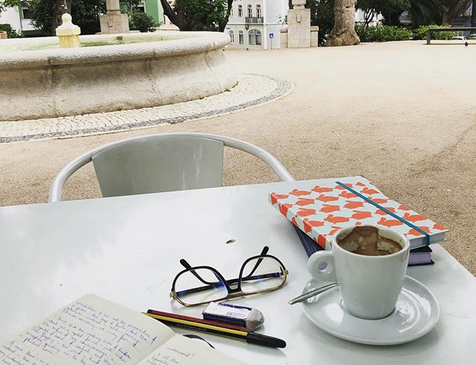

I’d strongly suggest that you do this on paper with a pen in your hand so that you can physically write any corrections or amendments you might want to go back and make at the end of this process. A hard copy edit is another potentially vital part of your editing process and combining these two aspects – paper and voice – is a pretty close approximation to the reader’s experience when they eventually, hopefully, come to read your work.

Some cuts feel painful, but you will always, eventually, be glad you made them. But expansion might also be a significant part of your editing – it’s not all about cutting, though cutting can create space for further development elsewhere.

Is it possible to over-edit? Yes, I think it is. It often seems to me that a certain style has become the default of ‘good’ writing in the English and American markets – quite utilitarian and spare style in which the adverb is your enemy and description is a potential waste of time. In her book of essays, Feel Free, Zadie Smith refers to the ‘puritan brevity of the American sentence’ on the one hand, and ‘the artificial naivety of the English sentence’ on the other, which perfectly encapsulates what I mean. Both are all well and good, and absolutely fine if it’s what you want to do, but let us at least do away with hierarchies of style and recognize that they can be both culturally specific and personally subjective.

With this in mind, I feel very strongly that writers should read widely outside of their own cultures, languages (by reading works in translation), experiences, genres, and times. There are many, many different ways to tell, and write, a story and none of them are ‘right’, you just have to find the best one for you and your story.

What you are working towards is the illusion of effortlessness, lightness, spontaneity, in a process that requires the opposite of those.